Can I use a rubble stone trench foundation for a heavy log cabin/ house

Blog Post

Choosing foundation materials: A subconscious decision?

We design a house from the inside out and engineer a house from the top down, but we build a house from the ground up. What are the most environmentally sensitive, durable materials?

[Editor's note: Robert Riversong, a Vermont builder, continues his 10-part series of articles taking design and construction to what he sees as radical or "root" concerns. Enjoy--and please share your thoughts. – Tristan Roberts]

5. Foundations – it all starts here: how do we begin?

From the Ground Up

We design a house from the inside out and engineer a house from the top down, but we build a house from the ground up. The foundation is, literally, the basis for everything else--and the old-timers used to say that a house is only as good as its foundation. When our shelters were simple, such as the log cabins of the American frontier, we could mark out our place on earth with four large stones and call that sufficient. But today, we expect much from a foundation. At its most basic, a foundation must couple a building to the ground, transferring gravity loads as well as the wind effects of uplift and overturning and the seismic effects of shear, sliding and collapse. A foundation must also resist lateral soil pressure, hydraulic pressure and frost expansion, and prevent water, water vapor and soil gas (radon) intrusion. It may also be expected to contain mechanical systems, create storage space or contribute to conditioned living space. And, from the design perspective, it creates the "footprint" of the house above--defining its size, shape and contours.

The Semiotics of the Basement

Beyond these mundane functions, the cellar symbolically represents descent, the unconscious, the past, the things we would rather keep hidden. Whatever we build also recreates the primary archetypes of consciousness but, except for the practitioners of the ancient arts of vastu (Hindu), feng shui (Chinese) and sacred geometry (Greek), we have forgotten the importance of aligning space with place, of balancing the inner with the outer, of harmonizing the seen with the unseen.

"We resonate at both cellular and consciousness levels with our environment. By creating an environment around us that is supportive to both our inner and our outer senses, we can enhance rather than alienate our human links with nature. Architecture, when employed as a means of embodying principles of universal harmony can sustain us rather than drain us, so that our homes become our havens, and our work places support our creativity."– John Koch, Bacchus Marsh, Australia

SUPPORT INDEPENDENT SUSTAINABILITY REPORTING

BuildingGreen relies on our premium members, not on advertisers. Help make our work possible.

See membership options »

A Pattern Language

The foundation also sets the pattern for the rest of the structure. If a primary design goal is to minimize a building's ecological footprint, then we must consider reducing the landscape footprint and the landscape impact--including site disruption, tree destruction, length of access, depth of excavation, amount of replacement fill required, alterations in site topography, and effects on the aesthetics and biotic community of the surrounding land.

The qualities of the site and soil should be reflected in our determination of appropriate foundation, including such elements as surface drainage topography, soil percolation capacity, seasonal water table, frost-heave susceptibility, subsoil depth and texture, and soil load bearing capacity.

Cast in Concrete

Finally, foundation materials must be locally available, cost-effective, durable, and ideally have a low embodied energy and global warming potential as well as being non-toxic to either occupants or the surrounding biotic community. Concrete, either cast-in-place or pre-cast or as concrete masonry units (CMUs) is the most commonly used foundation material but also the second most used substance on earth (after water), and it contains extraordinary embodied fossil fuel energy, and a primary contributor to global warming. Concrete has many advantages as a foundation material, but should be used as sparingly as possible.

Creative Alternatives

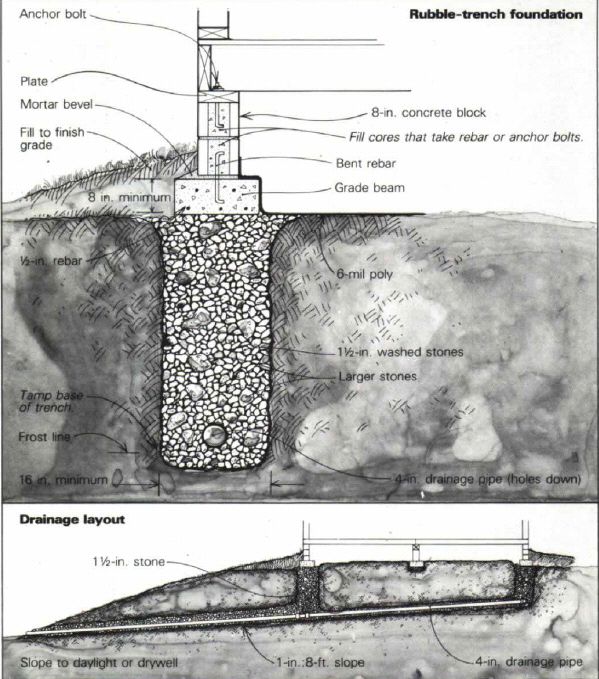

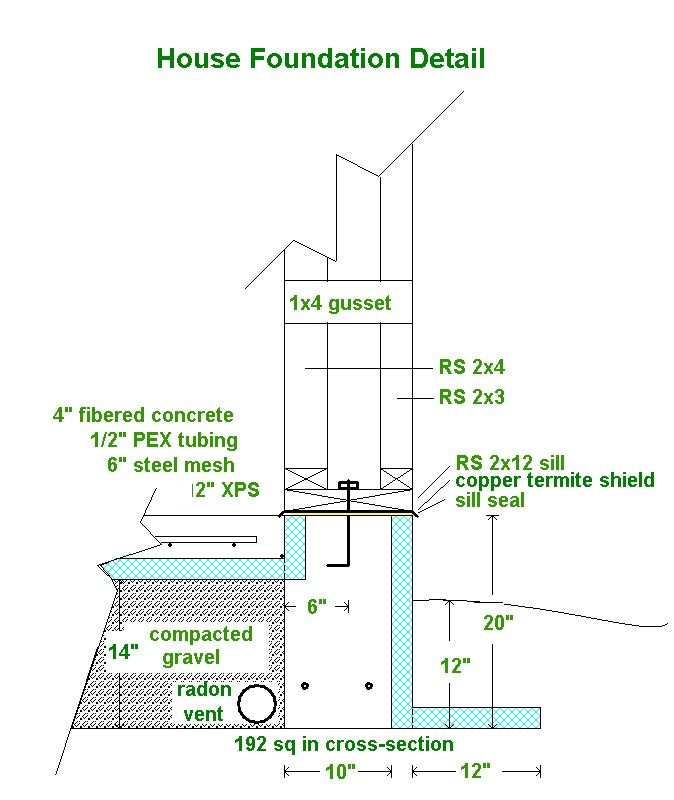

For these reasons, I have tended to prefer either rubble-trench foundations (à la Frank Lloyd Wright) or frost-protected shallow grade beams. The dramatic reduction in both excavation and concrete volume that these systems allow can justify the use of an insulated concrete slab if it has the multiple purposes of finished floor (tinting the mix is the least expensive way to do this), radiant heat source, and solar thermal mass storage. I use the rubble trench on wet or poorly drained sites and the frost-protected shallow foundation (FPSF) on flat sites with well-drained soils. The FPSF is now accepted in the international residential code and the design guide is downloadable through NAHB Research Center (toolbase.org).

When I have to build a full foundation, such as a walk-out basement on a heavily sloped site, I prefer the multiple advantages of the ThermoMass®insulation system (or CIC: concrete/insulation/concrete), which has been used for 30 years in large commercial and industrial applications (including precast and tilt-up) and is now being offered (with free technical assistance and training) for cast-in-place residential foundations. This system puts XPS--from 1" to 4" thick--midline in the concrete forms, held in place and tied to both wythes of concrete with 120,000 psi tensile-strength fiberglass rods 12" on center. This offers the strength of a full 8" concrete wall but with a capillary and thermal break that's protected from UV, insects, physical damage and fire exposure. It also offers almost the same dynamic thermal mass advantage of exterior-insulated concrete. It does, however, require a concrete pumper and a particular mix to fill the 4" form spaces.

Other, less conventional foundation options that are available for consideration include the All-Weather Wood foundation (pressure-treated sills, framing & plywood on a crushed stone base), insulated pre-cast concrete walls (that require heavy shipping), and the increasingly popular Insulated Concrete Forms (ICFs). But the latter puts the foam in the worst possible location--both outside and inside, where it's vulnerable to all the potential dangers--and provides little dynamic thermal mass factor.

Other somewhat more green ICF products include Rastra (recycled EPS/cement), Faswall (wood/cement with mineral wool inserts), and Durisol (wood/cement with mineral wool inserts), which are breathable, fire and insect-resistant systems that can be cut and machined like wood, hold fasteners, and make good substrates for stucco or plaster. Mineral wool, more commonly available in Canada than the U.S., is also a greener option for foundation insulation on conventional poured concrete or CMU walls. While it's not rated for subslab applications, it's apparently being used in Europe for that purpose.

Protection from the Storm

There are many foundation waterproofing products available today, but I prefer brush-on UGL Drylok latex masonry sealer for its ease of application, concrete-grey appearance, and vapor permeance. As with all parts of a thermal envelope (that's the next installment in this series), a foundation should be able to breathe. On a SFPF with exterior XPS, I trowel on 1/8" of surface bonding cement over ½" hardware cloth for protection and aesthetic.

Setting the Stage

So, even though a cellar might represent the unconscious domain of the archetypical inner sanctum, building "green" requires that we not choose materials and methods unconsciously. As the basis for everything constructed above it, a foundation should set the stage for the design goals of any building project.

1. Context – land, community & ecology

2. Design – elegant simplicity, the Golden Mean

3. Materials – the Macrobiotics of building: natural, healthy and durable

4. Methods – criteria for appropriate technology

5. Foundations – it all starts here: how do we begin?

6. Envelope – shelter from the storm, our third skin

7. HVAC – maintaining comfort, health and homeostasis

8. Energy & Exergy – sources and sinks

9. Hygro-Thermal – the alchemy of mass & energy flow

10. Capping it All Off – hat & boots and a good sturdy coat

copyleft by Robert Riversong: may be reproduced only with attribution for non-commercial purposes

Robert Riversong has been a pioneer in super-insulated and passive solar construction, an instructor in building science and hygro-thermal engineering, a philosopher, wilderness guide and rites-of-passage facilitator. He can be reached at HouseWright (at) Ponds-Edge (dot) net. Some of his work can be seen at BuildItSolar.com (an article on his modified Larsen Truss system), GreenHomeBuilding.com (more on the Larsen Truss), GreenBuildingAdvisor.com (a case study of a Vermont home), and Transition Vermont (photos).

Published May 30, 2011 Permalink Citation

(2011, May 30). Choosing foundation materials: A subconscious decision?. Retrieved from https://www.buildinggreen.com/blog/choosing-foundation-materials-subconscious-decision

Add new comment

To post a comment, you need to register for a BuildingGreen Basic membership (free) or login to your existing profile.